MM Curator summary

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

[MM Curator Summary]: Hospitals make a valid point- spending Medicaid bucks on food sounds great, as long as the actual healthcare needs are being met first.

It wasn’t exactly an emergency, but Michael Reed, a security guard who lives in Watts, had back pain and ran out of his blood pressure medication. Unsure where else to turn, he went to his local emergency room for a refill.

Around the same time, James Woodard, a homeless man, appeared for his third visit that week. He wasn’t in medical distress. Nurses said he was likely high on meth and just looking for a place to rest.

In an overflow tent outside, Edward Green, a restaurant cook, described hearing voices and needing medication for his bipolar disorder.

The three patients were among dozens who packed the emergency room at MLK Community Hospital, a bustling health care complex in South Los Angeles reincarnated from the old hospital known as “Killer King” for its horrific patient care. The new campus serves the 1.3 million residents of Willowbrook, Compton, Watts, and other neighborhoods — a heavily Black and Latino population that suffers disproportionately high rates of devastating chronic conditions like diabetes, liver disease, and high blood pressure.

Arguably, none of the three men should have gone, on this warm April afternoon, to the emergency room, a place intended to address severe and life-threatening cases — and where care is extremely expensive.

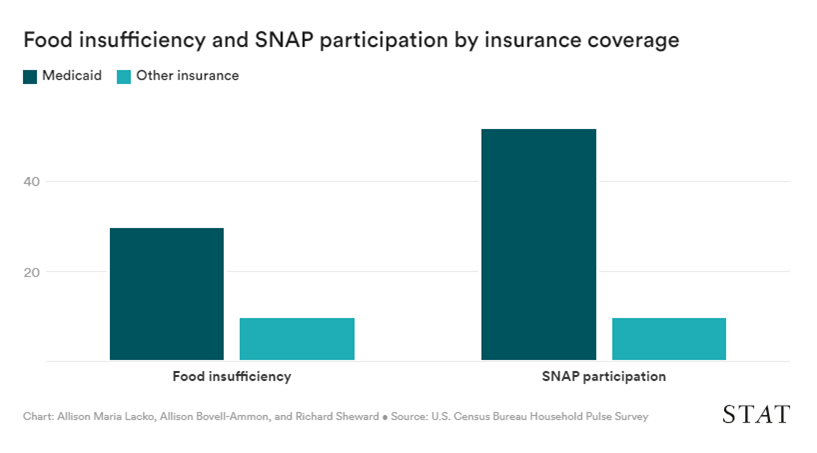

But patients and doctors say it is nearly impossible to find a timely medical appointment or receive adequate care in the impoverished community, where fast food is easy to come by and fresh fruits and vegetables are not. Liquor stores outnumber grocery stores, and homeless encampments are overflowing. A staggering 72% of patients who receive care at the hospital rely on Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program for low-income people.

“For some people, the emergency room is a last resort. But for so many people who live here, it’s literally all there is,” said Dr. Oscar Casillas, who runs the department. “Most of what I see is preventable — preventable with normal access to health care. But we don’t have that here.”

The community is short 1,400 doctors, according to Dr. Elaine Batchlor, the hospital’s CEO, who said her facility is drowning under a surge of patients who are sicker than those in surrounding communities. For instance, the death rate from diabetes is 76% higher in the community than in Los Angeles County as a whole, 77% higher for high blood pressure — an early indicator of heart disease — and 50% higher for liver disease.

But dramatic changes are afoot that could herald improvements in care — or cement the stark health disparities that persist between rich and poor communities.

Gov. Gavin Newsom is spearheading a massive experiment in Medi-Cal, pouring nearly $9 billion into a five-year initiative that targets the sickest and costliest patients and provides them with nonmedical benefits such as home-delivered meals, money for housing move-in costs, and home repairs to make living environments safer for people with asthma.

The concept — which is being tested in California on a larger scale than anywhere else in the country — is to improve patient health by funneling money into social programs and keeping patients out of costly institutions such as emergency departments, jails, nursing homes, and mental health crisis centers.

The initiative, known as CalAIM, sounds like an antidote to some of the ills that plague MLK. Yet only a sliver of its patients will receive the new and expensive benefits.

Just 108 patients — the hospital treats about 113,000 people annually — have enrolled since January. Statewide, health insurers have signed up more than 97,200 patients out of roughly 14.7 million Californians with Medi-Cal, according to state officials. And while a growing number of Medi-Cal enrollees are expected to receive the new benefits in the coming years, most will not.

Top state health officials argue that the broader Medi-Cal population will benefit from other components of CalAIM, which is a multipronged, multiyear effort to boost patients’ overall physical and mental health. But doctors, hospital leaders, and health insurance executives are skeptical that the program will fundamentally improve the quality of care for those not enrolled — including access to doctors, one of the biggest challenges for Medi-Cal patients in South Los Angeles.

“The state is now saying it will allow Medicaid dollars to be spent on things like housing and nutritious food — and those things are really important — but they’re still not willing to pay for medical care,” Batchlor said.

Batchlor has been lobbying the Newsom administration and state lawmakers to fix basic health care for the state’s poorest residents. She believes that increasing payments for doctors and hospitals that treat Medi-Cal patients could lead to improvements in both quality and access. The state and the 25 managed-care insurance plans it pays to provide health benefits to most Medi-Cal enrollees reimburse providers so little for care that it perpetuates “racism and discrimination,” she said.

Batchlor said the hospital gets about $150, on average, to treat a Medi-Cal patient in its emergency room. But it would receive about $650 if that patient had Medicare, she said, while a patient with commercial health insurance would trigger a payment of about $2,000.

The hospital brought in $344 million in revenue in 2020 and spent roughly $330 million on operations and patient care. It loses more than $30 million a year on the emergency room alone, Batchlor said.

Medicaid is generally the lowest payer in health care, and California is among the lowest-paying states in the country, experts say.

“The rates are not high enough for providers to practice. Go to Beverly Hills and those people are overdosing on health care, but here in Compton, patients are dying 10 years earlier because they can’t get health care,” Batchlor said. “That’s why I call it separate and unequal.”

Newsom in September vetoed a bill that would have boosted Medi-Cal payment rates for the hospital, saying the state can’t afford it. But Batchlor isn’t giving up. Nor are other hospitals, patient advocates, Medi-Cal health insurers, and the state’s influential doctors’ lobby, which are working to persuade Newsom and state lawmakers to pony up more money for Medi-Cal.

It’ll be a tough sell. Newsom’s top health officials defend California’s rates, saying the state has boosted pay for participating providers by offering bonus and incentive payments for improvements in health care quality and equity — even as the state adds Medi-Cal recipients to the system.

“We’ve been the most aggressive state in expanding Medi-Cal, especially with the addition of undocumented immigrants,” said Dustin Corcoran, CEO of the California Medical Association, which represents doctors and is spearheading a campaign to lobby officials. “But we have done nothing to address the patient access side to health care.”

***

The hospital previously known as Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center was forced to shut down in 2007 after a Los Angeles Times investigation revealed the county-run hospital’s “long history of harming, or even killing, those it was meant to serve.” In one well-publicized case, a homeless woman was writhing in pain and vomiting blood while janitors mopped around her. She later died.

MLK Community Hospital rose from its ashes in 2015 as a private, nonprofit safety-net hospital that runs largely on public insurance and philanthropy. Its state-of-the-art facilities include a center to treat people with diabetes and prevent their limbs from being amputated — and the hospital is trying to reach homeless patients with a new street medicine team.

Still, decades after the deadly 1965 Watts riots spurred construction of the original hospital — which was supposed to bring high-quality health care to poor neighborhoods in South Los Angeles — many disparities persist.

Less than a mile from the hospital, 60-year-old Sonny Hawthorne rattled through some trash cans on the sidewalk. He was raised in Watts and has been homeless for most of his adult life, other than stints in jail for burglary.

He hustles on his bike doing odd jobs for cash, such as cleaning yards and recycling, but said he has trouble filling out job applications because he can’t read. Most of his day is spent just surviving, searching for food and shelter.

Hawthorne is one of California’s estimated 173,800 homeless residents, most of whom are enrolled in Medi-Cal or qualify for the program. He has diabetes and high blood pressure. He had been on psychotropic medicine for depression and paranoia but hasn’t taken it in months or years. He can’t remember.

“They wanted me to come back in two weeks, but I didn’t go,” he said of an emergency room visit this year for chronic foot pain associated with diabetes. “It’s too much responsibility sometimes.”

Hawthorne’s chronic health conditions and homelessness should qualify him for the CalAIM initiative, which would give him access to a case manager to help him find a primary care doctor, address untreated medical conditions, and navigate the new social services that may be available to him under the program.

But it’s not up to him whether he receives the new benefits.

The state has yielded tremendous power to Medi-Cal’s managed-care insurance companies to decide which social services they will offer. They also decide which of their sickest and most vulnerable enrollees get them.

One benefit all plans must offer is intensive care management, in which certain patients are assigned to case managers who help them navigate their health and social service needs, get to appointments, take their medications regularly, and eat healthy foods.

Plans can also provide benefits from among 14 broad categories of social services, such as six months of free housing for some homeless patients discharged from the hospital, beds in sobering centers that allow patients to recover and get clean outside the emergency room, and assistance with daily tasks such as grocery shopping.

L.A. Care Health Plan, the largest Medi-Cal managed-care insurer in Los Angeles County, with more than 2.5 million enrollees, is contracting with the hospital, which will provide housing and case management services under the initiative. For now, the hospital is targeting patients who are homeless and repeat emergency room visitors, said Fernando Lopez Rico, who helps homeless patients get services.

So far, the hospital has referred 78 patients to case managers and enrolled 30 other patients in housing programs. Only one has been placed in permanent housing, and about 17 have received help getting temporary shelter.

“It is very difficult to place people,” Lopez Rico said. “There’s almost nothing available, and we get a lot of hesitancy and pushback from private property owners not wanting to let these individuals or families live there.”

Patrick Alvarez, 57, has diabetes and was living in a shed without running water until July, when an infection in his feet grew so bad that he had several toes amputated.

The hospital sent him to a rehabilitation and recovery center, where he is learning to walk again, receiving counseling, and looking for permanent housing.

If he finds a place he can afford, CalAIM will pay his first month’s and last month’s rent, the security deposit, and perhaps even utility hookup fees.

But the hunt for housing, even with the help of new benefits, is arduous. A one-bedroom apartment he saw in September was going for $1,600 a month and required a deposit of $1,600. “It’s horrible, I can’t afford that,” he said.

Hawthorne needs help just as badly. But he’s unlikely to get it since he doesn’t have a phone or permanent address — and wouldn’t be easy for the hospital to find. The homeless encampments where he lives are routinely cleared by law enforcement officials.

“We have so many more people who need help than are able to get it,” Lopez Rico said. “There aren’t enough resources to help everyone, so only some people get in.”

***

L.A. Care has referred about 28,400 members to CalAIM case managers, roughly 1% of its total enrollees, according to its CEO, John Baackes. It is offering housing, food, and other social services to even fewer: about 12,600 people.

CalAIM has the potential to dramatically improve the health of patients who are lucky enough to receive new benefits, Baackes said. But he isn’t convinced it will save the health care system money and believes it will leave behind millions of other patients — without greater investment in the broader Medi-Cal program.

“Access is not as good for Medi-Cal patients as it is for people with means, and that is a fundamental problem that has not changed with CalAIM,” Baackes said.

Evidence shows that basic Medi-Cal patient care is often subpar.

Year-over-year analyses published by the state Department of Health Care Services, which administers Medi-Cal, have found that, by some measures, Medi-Cal health plans are getting worse at caring for patients, not better. Among the most recent findings: The rates of breast and cervical cancer screenings for women were worse in 2020 than 2019, even when the demands that covid-19 placed on the health care system were factored into the analysis. Hospital readmissions increased, and diabetes care declined.

“The impact of covid is real — providers shut down — but we also know we need a lot of improvement in access and quality,” said State Medicaid Director Jacey Cooper. “We don’t feel we are where we should be in California.”

Cooper said her agency is cracking down on Medi-Cal insurance plans that are failing to provide adequate care and is strengthening oversight and enforcement of insurers, which are required by state law to provide timely access to care and enough network doctors to serve all their members.

The state is also requiring participating health plans to sign new contracts with stricter quality-of-care measures.

Cooper argues CalAIM will improve the quality of care for all Medi-Cal patients, describing aspects of the initiative that require health plans to hook patients up with primary care doctors, connect them with specialty care, and develop detailed plans to keep them out of expensive treatment zones like the emergency room.

She denied that CalAIM will leave millions of Medi-Cal patients behind and said the state has increased incentive and bonus payments so health care providers will focus on improving care while implementing the initiative.

“CalAIM targets people who are homeless and extremely high-need, but we’re also focusing on wellness and prevention,” she told KHN. “It really is a wholesale reform of the entire Medicaid system in California.”

A chorus of doctors, hospital leaders, health insurance executives, and health care advocates point to Medi-Cal reimbursement rates as the core of the problem. “The chronic condition in Medi-Cal is underfunding,” said Linnea Koopmans, CEO of the Local Health Plans of California.

Although the state has restored some previous Medi-Cal rate cuts, there’s no move to increase base payments for doctors and hospitals. Cooper said the state is using tobacco tax dollars and other state money to attract more providers to the system and to entice doctors who already participate to accept more Medi-Cal patients.

When Newsom vetoed the bill to provide higher reimbursements primarily for emergency room care at MLK, he said the state cannot afford the “tens of millions” of dollars it would cost.

MLK leaders vow to continue pushing, while other hospitals and the powerful California Medical Association plot a larger campaign to draw attention to the low payment rates.

“Californians who rely on Medi-Cal — two-thirds of whom are people of color — have a harder time finding providers who are willing to care for them,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, a spokesperson for the California Hospital Association.

For Dr. Oscar Casillas at MLK, the issue is critical. Although he’s a highly trained emergency physician, most days he practices routine primary care, addressing fevers, chronic foot and back pain, and missed medications.

“If you put yourself in the shoes of our patients, what would you do?” asked Casillas, who previously worked as an ER doctor in the affluent coastal city of Santa Monica. “There’s no reasonable access if you’re on Medi-Cal. Most of the providers are by the beach, so emergency departments like ours are left holding the bag.”

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.