MM Curator summary

Louisiana HHS officials have now sent the 2nd in a series of letters notifying members they need to submit documentation to maintain their Medicaid coverage.

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

Louisiana residents who are enrolled in Medicaid may begin receiving letters from the Louisiana Department of Health informing them that their coverage will end when the federal public health emergency declaration for COVID-19 is lifted.

These “preclosure” letters are among the first public-facing steps Medicaid has taken towards a return to normal operations after a year and a half of emergency response.

The federal public health emergency, which underpins that emergency response, is expected to last until at least the end of 2021. But when it does end, the state’s Medicaid office will be faced with a backload of renewals and eligibility checks.

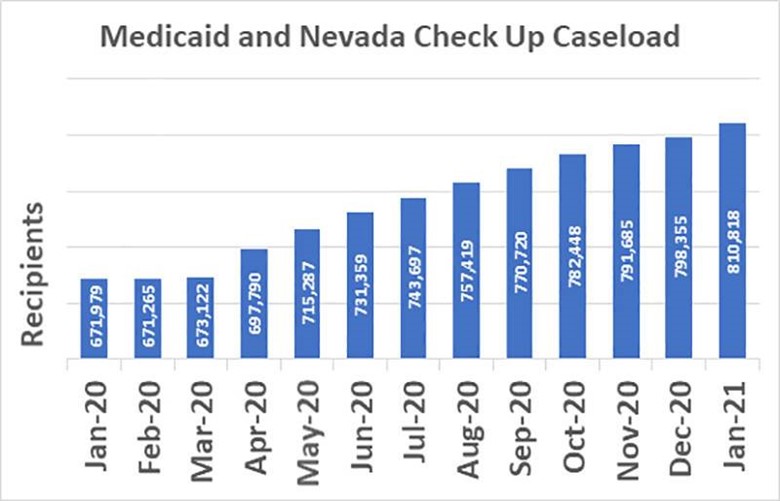

Over the course of the pandemic, the number of Louisiana Medicaid recipients has grown substantially. Emergency programs have supported much of that growth the past year, but the federal government has asked states to begin planning how to wind down emergency measures, which means, in large part, resuming eligibility checks and disenrolling recipients.

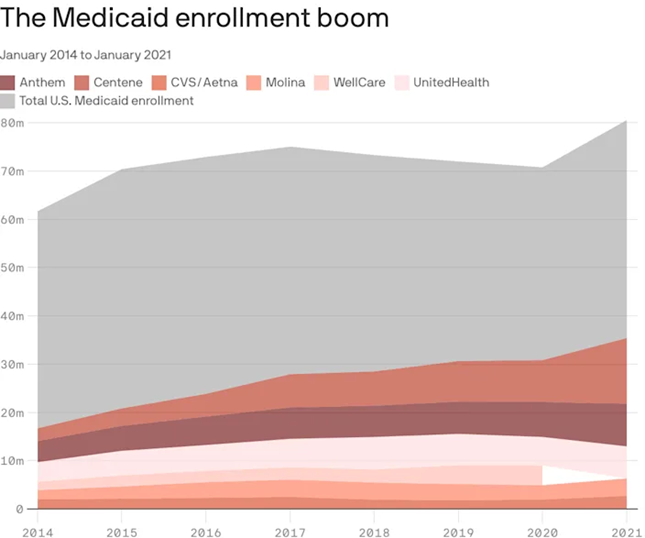

Most of Medicaid’s growth has come from the Affordable Care Act’s expansion program, which covers low-income adults.

In March 2020, 483,000 people received Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act’s expansion, and 1.6 million people were enrolled in total. By May 2021, those numbers were 639,000 and 1.9 million respectively — roughly 40 percent of the state’s residents.

That mirrors a national trend. According to a report released this week by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, fully a quarter of the U.S. population is now enrolled in Medicaid.

That rise comes partly because of job losses caused by the pandemic, and partly because over the course of the pandemic, Louisiana, like every other state, has virtually halted all Medicaid disenrollments.

That’s important because under normal circumstances, recipients would be subject to regular eligibility checks.

Those eligibility checks happen in several ways: On the most basic level, Medicaid recipients need to renew their coverage every year, either online or over the phone.

But Louisiana conducts the extra step of quarterly wage checks to determine whether someone has exceeded income limits over the course of the year. The checks are automated using a Louisiana Workforce Commission database, and when someone does not pass a check, they receive a letter asking them to provide more information or contest the decision.

The eligibility checks and renewals have been paused by a federal policy related to pandemic Medicaid funding. The cost of Medicaid is split between the state and the federal government, and during the pandemic, the federal government has paid for a larger share. The agreement required states to maintain their Medicaid rolls, with a few narrow exceptions for those who died or moved out of state. That will soon be coming to an end.

In December, the federal government asked states to begin planning for renewed eligibility checks. That guidance was released under the Trump administration, and according to a statement provided by Medicaid to the Lens, “we are prepared with an operational plan. Additional guidance from [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] is forthcoming.”

Churn

Many of the people who are disenrolled may in fact no longer be eligible for Medicaid benefits. But the return to eligibility checks also creates the risk of disenrolling people who are eligible, a phenomenon known as “churn.”

Churn, in which eligible people repeatedly lose and reapply for coverage because of administrative procedures, predates the pandemic, said Stacey Roussell, the policy director of the Louisiana Budget Project, a left-leaning policy think tank.

“What you find in the income level of people who qualify for the Medicaid expansion is, it’s very common throughout the year to have fluctuations in income,” Roussell says. “There are parts of the year where maybe their household need is greater, and they’re going to pick up extra shifts.”

So even though a household may qualify for Medicaid on the basis of its annual income, a quarterly wage check may flag a seasonal fluctuation — like the spring tourist season — as a reason to end eligibility. When that happens, Medicaid sends the recipient a letter asking for more information.

But the recipient has only 10 days to respond, starting from the date the letter was mailed. That tight window, according to an April policy brief from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “rais[es] concerns about the limited time allowed to gather appropriate documentation.”

LDH has published similar conclusions: a 2019 report to the state legislature found that 85 percent of Medicaid eligibility cases were closed because a recipient failed to respond to a request for information.

“These closures do not necessarily indicate ineligibility for Medicaid benefits, and individuals may return to eligibility if supporting information is provided,” the report reads.

The HHS policy brief also noted that churn may lead to higher per-patient Medicaid costs, both because recipients with sporadic coverage are less likely to seek preventative care, which is generally less expensive than emergency care, and because disenrolling and re-enrolling recipients creates high administrative costs for states.

Louisiana enrollees will have months before the end of the pandemic to respond to or contest Medicaid’s inquiries. Still, proving eligibility can present its own challenges, especially for people who may have lost shift work because of the pandemic.

160,000 facing end of benefits

In a December report produced by the legislature’s Joint Medicaid Oversight Committee, LDH estimated that 160,000 people would become ineligible as a result of reinstating eligibility checks. That’s more than the total growth during the pandemic to that point.

However, said Courtney Foster, the Louisiana Budget Project’s Medicaid policy advocate, “we have some issues with this number, because they estimate based on the number of people disenrolled at prior [quarterly wage checks]… [which] does not automatically mean they were ineligible. The number could set an expectation from the legislature or others that they should expect at least that number of people to be disenrolled immediately when the [Public Health Emergency] ends.”

“We want to make sure that, post COVID, as people have delayed care, that they’re as connected to the available health insurance as possible, or else I think we will see an increase in medical debt, or showing up in emergency rooms in need of care that they’ve forgone because they didn’t have health insurance,” said Roussell. “There’s a lot at stake going into 2022 and getting it right.”

A January report from the Commonwealth Fund warned that “erroneous disenrollment could affect tens of millions of Medicaid enrollees” across the country.

In the December report, LDH says that it expects an “overwhelming workload of over 500,000 tasks that are anticipated at the end of the [Public Health Emergency].” In that report, LDH expected to complete the transition process by six months after the end of the public health emergency.

That began with letters sent out in January to those who were up for renewal, “asking them to renew their coverage or to supply additional information,” according to a statement attributed to Medicaid provided by LDH spokesman Kevin Litten.

The letters sent this month are a follow up to those initial communications.

“Starting this month, if members do not respond to these letters, they will lose their coverage when the public health emergency ends,” according to the Medicaid statement Litten provided. “At the end of the public health emergency, members will receive one final letter alerting them to their final date of health care coverage.”

There are steps that the state could take to soften the blow. One of them, expanding Medicaid coverage for people who have just given birth using funding from the American Rescue Plan, died in the 2021 legislative session. It’s also unclear how the legislature’s decision to set the Medicaid budget $24 million below Gov. John Bel Edwards’ original budget proposal will impact recipients.

Roussell said that her organization’s goal is to see the process slow down and focus on people who still need coverage.

“If you’re entering into it just to say, ‘we must get everybody who is ineligible off the rolls as fast as possible,’ then you’re willing to sacrifice a huge number of people who may still be eligible,” she said. “We want to say, let’s first make sure that everybody has the best chance possible to show that they’re eligible.”