MM Curator summary- Georgia has gone from reporting 75% of CMS program measures to only 25%.

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

Clipped from: https://www.albanyherald.com/news/georgia-is-not-reporting-adequate-medicaid-peachcare-data/article_6122e664-4851-11eb-b483-7feaf358cb7c.html

ATLANTA — Nine years ago, Georgia reported ample data to the feds on the health care quality of its Medicaid and PeachCare programs.

In fact, a federal report at that time praised Georgia’s “proactive role in designing its data systems to support quality measurement.”

For seven more years, Georgia continued to be near the top of the data-reporting charts for what’s called the Core Set. It consistently submitted information about how its Medicaid program and its children’s health insurance, or CHIP program (known as PeachCare in Georgia), were delivering care.

No matter how well or poorly the state performed during those years, it submitted the data under the voluntary set-up.

But according to a Georgia Health News analysis, for the last two years, Georgia reported only a fraction of the information the federal Core Set requested.

Among the items not reported are rates of timely post-natal care, blood-sugar testing rates for diabetes, rates of patients using opioids at high doses, rates of hypertension control, and most mental health measures.

With 59 metrics, the Core Set aims to help states “monitor and improve the quality of health care” for Medicaid and CHIP plans, according to a 2018 press release from Seema Verma, administrator of the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The Core Set is part of a push to improve transparency and accountability for states’ health insurance programs.

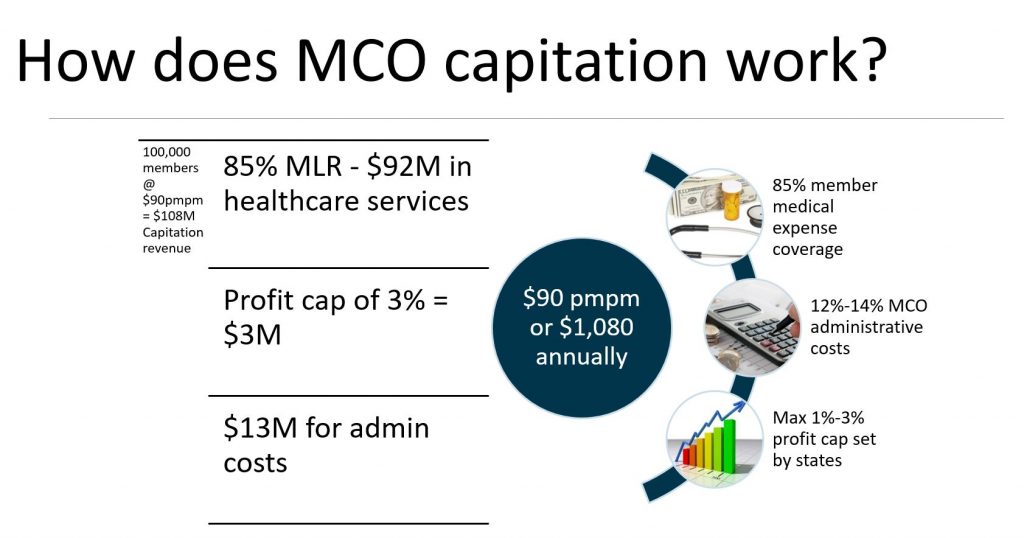

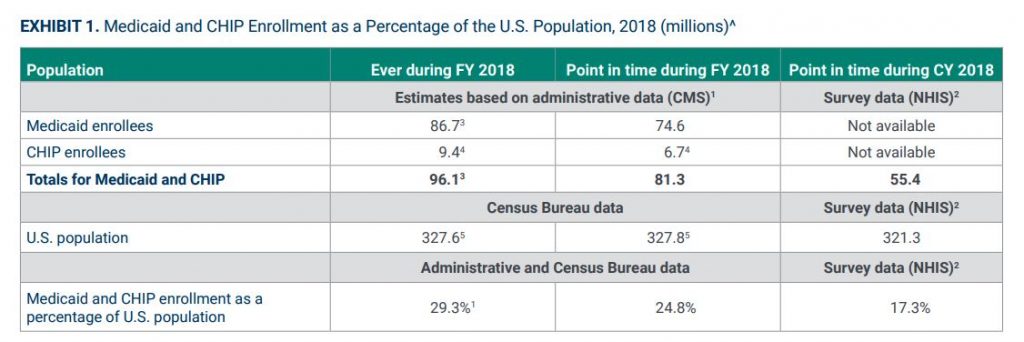

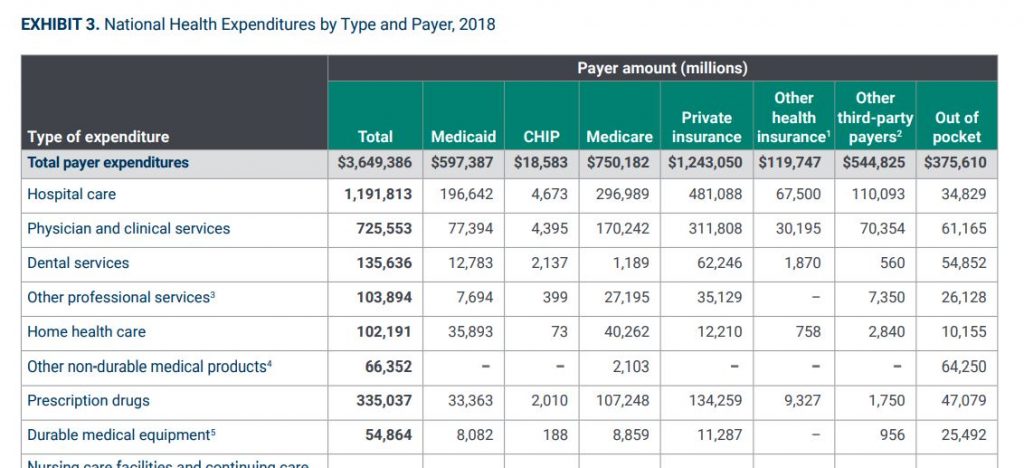

Medicaid and PeachCare cover about 2 million Georgians, mostly children. Those kids and some adults are part of a Georgia Families program that has been served by four insurance companies – Amerigroup, CareSource, Peach State and WellCare – which the government pays a total of $4 billion annually.

In 2011, the first year of the Core Set program, Georgia submitted the most performance measures of any state, 18 out of 24 requested.

For the latest data submission, GHN found that the state reported only eight of the 33 performance measures requested for adult measures, and just 13 of the 25 children’s measures.

When asked about the change in approach to reporting, Georgia’s Department of Community Health said the federal methodology was not sound because each state’s reporting method could vary.

States may use different methods in preparing the data, a weakness that the Core Set’s own documents acknowledge.

“In 2018, DCH reviewed the existing set of measures and determined that we needed a method that would allow us to benchmark ourselves to other Medicaid plans across the nation,” DCH Press Secretary Fiona Roberts said via email. “It was imperative that the benchmark was based on measures that were uniformly defined and populated for all Medicaid plans.”

Neighboring Southeastern states such as Alabama, South Carolina and Tennessee continue to lead in reporting the Core Set, while Georgia is now at the bottom of the data charts alongside Nebraska and South Dakota.

“Not reporting [the data] publicly, to me, is kind of a red flag,” David Machledt, senior policy analyst at the National Health Law Program, which aims to increase health care access, said. “Why should that not be open to public scrutiny?

“In general, almost every other state is on a trajectory where they’re reporting more measures [to the Core Set], not fewer, over time.”

Currently, reporting the federal core set is voluntary, although reporting all children’s health measures and adult mental health measures will become mandatory in 2024.

“If there are quality metrics that aren’t being met and we as the public can look and see where Georgia is falling short, we can hold our state decision-makers accountable,” Laura Colbert, executive director of the consumer advocacy group Georgians for a Healthy Future, said. “The greater the state reports, the better.”

Erica Fener Sitkoff, executive director of Voices for Georgia’s Children, an advocacy organization, said Medicaid and PeachCare cover half the children in the state.

“There needs to be some public accountability for the outcomes of those programs so that advocates, parents, and health care providers have visibility into how well they’re operating and can advocate for change,” Sitkoff said.

Jesse Weathington, executive director of the Georgia Quality Healthcare Association, an industry trade group, said that the four managed care companies “report reams of data on our performance to DCH on a consistent basis.”

Aside from the Core Set, DCH continues to publish performance data on its website each year, but the information is difficult to find. This year’s annual report on each of the four managed care companies included only 20 health indicators, compared to last year’s 49. These annual charts allow policymakers to view how each of the four companies delivered health care.

“For the 2019 reporting period, we reported on 20 measures total, 17 of which were Core Set measures,” Roberts said. “We are able to compare our performance on these measures to nationally recognized benchmarks and appropriately align them with internal performance efforts.”

The 2020 report omitted key data on lead exposure screening for children, opioid use, post-partum care, eye exams for diabetics, and hypertension control rates, among other indicators. Prior annual reports included easy-to-use comparative tables with star ratings based on national benchmarks for each of these health metrics.

This year the only way to find most of the data is by searching five different lengthy PDFs, found two-thirds of the way down the DCH’s Medicaid Quality webpage, and then compiling the data.

“Shining a light on where the program is meeting the mark and where it’s fallen short and still needs some improvement would actually be important for helping folks understand why the Medicaid program needs to exist,” said Colbert.

Georgia has cut from nine to three the number of maternal health care indicators it publishes in its internal Medicaid quality reports. Medicaid covers about half of births in Georgia, a state with a well-known maternal mortality crisis.

Georgia changed its approach to reporting Medicaid quality data within its own documents and to the federal government two years ago. Georgia’s most recent annual state reports published information on only three maternal health indicators:

♦ Timeliness of prenatal care;

Local Newsletter

Get the Local News headlines from the Albany Herald delivered daily to your email inbox.

Please enter a valid email address.

Manage your lists

♦ Percentage of infants with low birthweight;

♦ Timeliness of post-natal care.

♦ The first two measures are featured in the state’s annual reports, but this year, for the first time, finding information about timeliness of post-natal care requires digging through five separate PDFs.

Missing entirely from the most recent annual reports are indicators the state formerly reported on, such as:

♦ Caesarean and elective delivery rates;

♦ Rates of mental health evaluation for pregnant women;

♦ Use of steroids during pregnancy;

♦ Frequency of post-partum care.

“These indicators that are no longer being publicly made available are really good at helping us figure out how we got there,” said Amber Mack, a research and policy analyst at Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia, referring to the state’s maternal mortality crisis.

Earlier this year, the state approved extending Medicaid coverage for low-income new mothers from two to six months after delivery.

“How are we going to track and see if timeliness of post-partum care has improved … especially compared to other states?” Mack said.

The maternal health measures Georgia does report show that the insurance companies delivering care to Medicaid and PeachCare members are behind national quality benchmarks for maternal care. The companies’ performance on timeliness of prenatal care ranks in the 49th percentile or below, according to a national health care quality measure the state uses.

The numbers the state reports to the federal Core Set also reflect a downward trend. The most recent report to the federal government stated that 67 percent of Georgia Medicaid members were getting timely prenatal care, in contrast to the 81 percent reported four years ago.

Georgia’s rates of low-birthweight deliveries appear to be rising, according to an analysis of the state’s data. The latest state data show the weighted average for the four companies at 9.45 percent, compared to 8.74 percent two years ago.

Only about two-thirds of Georgia mothers on Medicaid are getting timely post-natal care. For the first time this year, data on post-partum care was not included in the state annual report.

Asked why Georgia reported only two maternal health measures to the latest federal Core Set, Roberts said the agency is prioritizing prenatal care, which “provides a sizable opportunity to improve care for both the mother and the infant.”

“It is our hope that these upstream efforts will help to reduce the percentage of live births that weighed less than 2,500 grams [roughly 5 pounds 8 ounces],” Roberts said in her email.

Georgia has cut back on mental health reporting within its state reports. Georgia’s Core Set data left out at least 10 other mental health measures that neighboring states reported. The reduction in reporting is concerning because the state faces “a behavioral crisis for our children,” said Sitkoff of Voices for Georgia’s Children.

Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, South Carolina and North Carolina reported almost all mental health measures to the latest data set, while Georgia reported only on depression screening.

Georgia’s Core Set report did not include data about Medicaid and CHIP that most other states’ reports did, such as:

— Antidepressant medication management;

— Whether adults and children seen at hospitals for substance abuse or mental illness received timely follow-up;

— How many children are prescribed multiple antipsychotics at the same time;

— How many children get treatments such as counseling for behavioral health issues when they are also prescribed an antipsychotic drug;

— Opioid use rates.

In the mental health category, Georgia’s latest state and federal annual reports included data only on screening for depression in adults and children. Detailed mental health performance data is available on the DCH website, but it is split across five separate PDFs, in contrast to prior years. These separate reports lack national benchmarks.

Finding information about how state insurance plans provide care to people with diabetes is also more difficult this year. Georgia reported only one of six requested diabetes or weight-related measures to the federal Core Set.

The state’s annual reports also cut from 12 to two the diabetes health measures it presented. Though the additional information is available this year, it is difficult to find and lacks national benchmarks, in contrast with past reports.

The state did not report information to the feds about rates of blood-sugar testing this year, although last year’s report showed a testing rate of 66.6 percent, third-lowest in the nation.

Medicaid 301$229.00

Medicaid 301$229.00