MM Curator summary

[MM Curator Summary]: Colorado will use $24M in COVID relief funds to grow the MH network.

The article below has been highlighted and summarized by our research team. It is provided here for member convenience as part of our Curator service.

Therapists, psychologists and others complain they have to wait months to get approval to take Medicaid patients – at a time when Colorado is trying to increase the number of providers who serve needy patients.

Woodland Park psychologist Chris Estep spent decades helping foster children and Colorado prison inmates with mental health issues, so when he opened a private practice two years ago, he wanted to take patients on Medicaid across the eastern half of the state.

He’s still waiting for permission after filing an application 14 months ago.

Estep, one of the few licensed psychologists who performs mental health and cognitive evaluations for kids all the way up to older adults with dementia, is allowed to take Medicaid patients in just three counties, despite wanting to serve a much broader region that would include Sterling and Pueblo. As a result, he’s had to turn down patients, or take them without getting Medicaid reimbursement.

His frustration with Colorado’s mental health system for the needy – in which mental health professionals have to enroll not just at the state Medicaid department but also contract with regional agencies that serve as middlemen between the state and the providers – is echoed across the industry.

And the anger over the complicated and slow process is rising among mental health workers at the same time the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, which oversees the Medicaid program, is touting a dramatic boost in providers who are accepting Medicaid patients. Increasing the number of providers has been a priority of Gov. Jared Polis’ administration in order to increase access to mental health care, and there is $24 million in federal coronavirus aid to put toward the effort.

But therapists, psychologists and others in private practice across the state are asking why – when the goal is to increase their numbers – is it so hard to get permission to join the Medicaid program? And they’re questioning whether the state’s numbers showing a surge in Medicaid providers are accurate.

“There are so many hurdles,” said Estep, who specializes in telehealth and wants to see patients in rural southeastern and northeastern Colorado. “It’s really disheartening. And it doesn’t even have to be this way.”

The state Medicaid department said it increased the number of mental health providers accepting Medicaid to 8,371 at the end of 2021, up from 6,185 two years ago. This is the number of individual people – not clinics or community mental health centers – who’ve been approved by a Regional Accountable Entity to receive Medicaid reimbursements. It’s a number tallied by an external agency, not the state.

The bump in providers is significant, but not enough to meet the need. During the coronavirus pandemic, Colorado has added about 350,000 people to the Medicaid program – and 30% of them are dealing with anxiety and other mental health issues, according to the department.

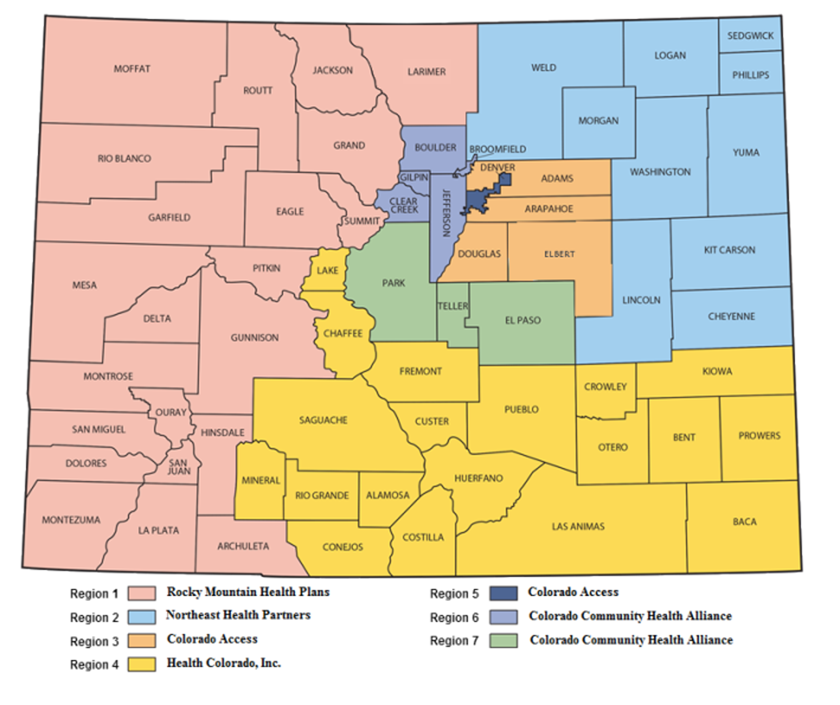

The first step for behavioral health professionals who want to take patients on Medicaid is to apply to the state department. The second is to submit paperwork to one or more of the seven regional entities that provide reimbursement.

Colorado is divided into seven regions run by agencies that contract with the state Medicaid division. Behavioral health providers who want to take patients on Medicaid must enroll first at the state department and then with the regional agencies. (Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing)

It’s relatively easy, mental health professionals say, to enroll as a Medicaid provider with the state – but it typically takes months to get credentials from one of the state’s seven Regional Accountable Entities, called RAEs.

A second tally by the Medicaid department tracks the number of clinics — from individual private practices to substance abuse clinics to community mental health centers with hundreds of professionals – that have enrolled in the state Medicaid program. This would include providers who enrolled with the Medicaid program but have yet to get approval from a regional agency to begin taking Medicaid patients.

The various numbers have led to criticism from mental health professionals and their advocates, who are casting doubt on whether the department knows the actual number of behavioral health providers who are currently seeing Medicaid patients. Ahead of this legislative session, they’ve fired off letters to state lawmakers asking for further review of the system.

State Medicaid officials acknowledge the way they’ve counted Medicaid providers – and their messaging around it – is confusing to the industry. One department memo, for example, included an erroneous calculation about the increase in providers. But the state argues that the numbers are correct.

“There are a lot of ways to count providers, which is why there is more than one number out there that we have used to count our progress,” said Cristen Bates, population health division director at the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing.

The state’s behavioral health setup is a so-called “managed-care” system, meaning the Medicaid program contracts with the regional agencies and gives them a lump sum to spend. The contracts mandate that 85% of the funding is spent on patient care, while the other 15% can go toward administrative costs and services such as data-tracking for providers.

The regional entities get to decide which mental health providers to allow into the network, and they can reject providers based on complaints of poor service or if the region already has enough of that type of provider. The regional agencies also set reimbursement rates, and can base them on supply and demand.

In a joint effort, state Medicaid officials and the regional entities are working to increase the number of mental health and substance abuse providers in the government insurance program. The state created a “recruitment tool kit” and the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies is about to send letters to psychologists, addiction professionals and others who aren’t taking Medicaid and ask them to sign up. The regional entities, meanwhile, are offering incentives, such as sign-on bonuses, thanks to the federal coronavirus aid.

“In Colorado we know there is an issue with accessing behavioral health services,” Bates said. “We are hearing clearly from the community that there needs to be more access.”

But those who’ve waited months for Medicaid credentials say the state needs to put more focus on smoothing out that process.

It varies by region, but it typically takes two or three months for regional entities to provide those credentials, said Stephanie Farrell, CEO of Left Hand Management, which helps mental health providers with the process as well as billing issues between providers and the regional entities.

Beacon Health Options, which runs two of the seven regional entities, often takes 10-14 months to credential providers, including Estep, the Woodland Park psychologist, Farrell said.

“And that is with no mistakes along the way by either the provider or the RAE in a very fragmented credentialing process,” she said. “Those providers cannot really do anything to improve access to care, so they should not be counted as enrolled.”

Beacon Health, which runs regions 2 and 4, did not return requests for comment from The Colorado Sun.

In one case, Farrell said, a regional entity denied a behavioral health professional who does neuropsychological testing for children on the autism spectrum, as well as counsels their families. The entity said it did not need any more providers of this type in the region, although Farrell said there is a severe shortage of such providers statewide. The decision is now on appeal, two years after the initial application.

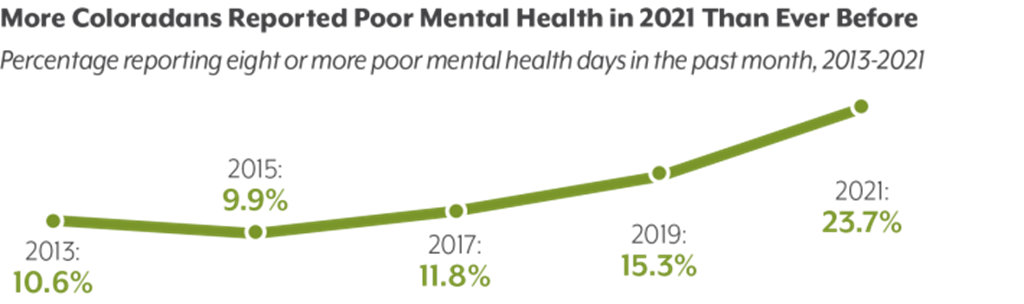

A chart from the Colorado Health Institute’s 2021 Colorado Health Access Survey shows the increase in the percentage of people reporting eight or more days of poor mental health during the previous month. (Provided by the Colorado Health Institute)

Farrell said it’s likely that the state numbers of providers taking Medicaid are inflated because when providers stop taking Medicaid, they often don’t bother with the long, convoluted process of terminating their enrollment with the regional entities. Instead, they just stop taking Medicaid patients, she said.

In November, multiple mental health providers told The Sun they were dropping Medicaid after a months-long paperwork issue that resulted in one of the regional entities, Colorado Community Health Alliance, ordering providers to return reimbursements they had already received for providing treatment. The health alliance reversed course after reports in The Sun and 9News, and pressure from state policymakers.

For Estep, the delay in his credentialing process has him wondering about all the patients who aren’t getting help. His psychological evaluations, which measure IQ, cognitive function and mental disorders, help people determine a course of treatment. In 2019, he started a part-time private practice, and knew from the start that he wanted to serve the state’s neediest population – particularly because those he worked with while they were behind bars would likely qualify for Medicaid upon release from prison.

He is allowed to see Medicaid patients from El Paso, Teller and Park counties, but the need for his services extends much farther, Estep said.

“It’s so strange,” he said. “The whole thing is stupid.”

The Colorado Sun has no paywall, meaning readers do not have to pay to access stories. We believe vital information needs to be seen by the people impacted, whether it’s a public health crisis, investigative reporting or keeping lawmakers accountable.

This reporting depends on support from readers like you. For just $5/month, you can invest in an informed community.

Clipped from: https://coloradosun.com/2022/01/18/mental-health-medicaid-delays/